Our research project at Lago Trasimeno is situated in central Italy (see Fig. 1 below):

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Italy_topographic_map-blank.svg

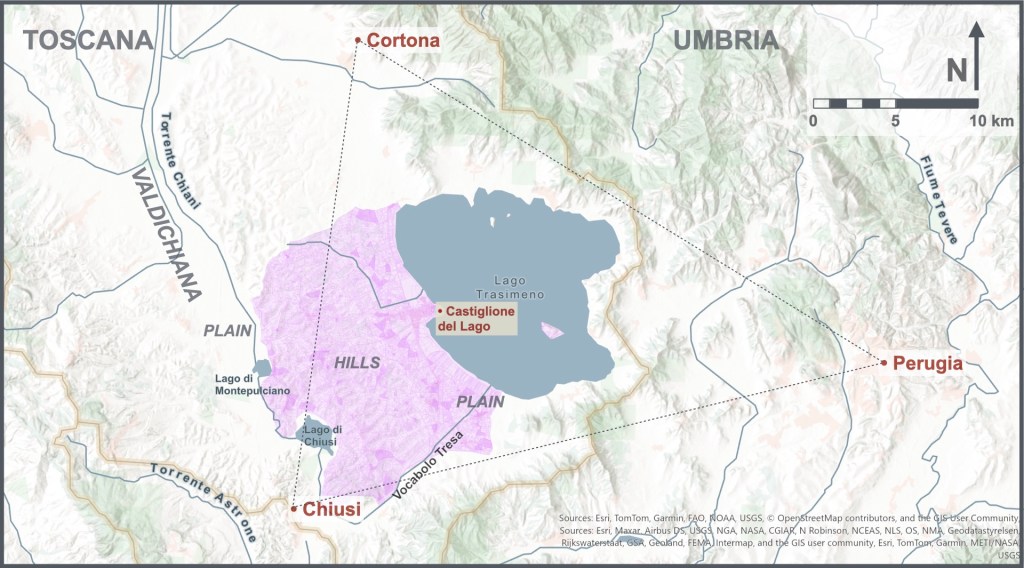

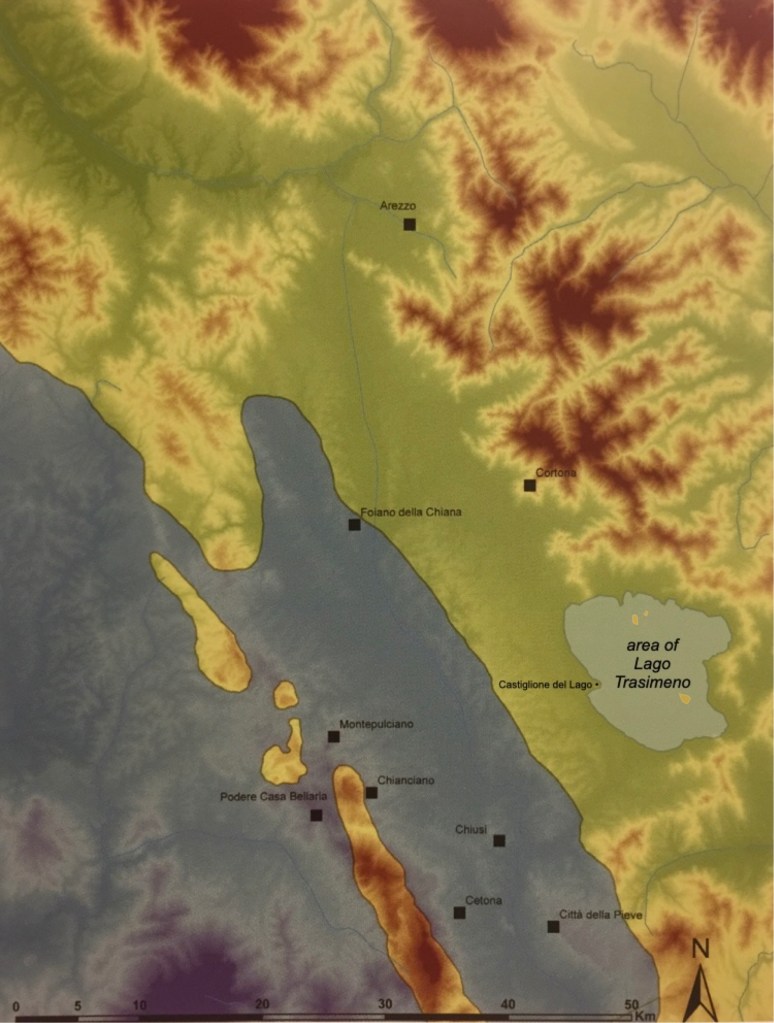

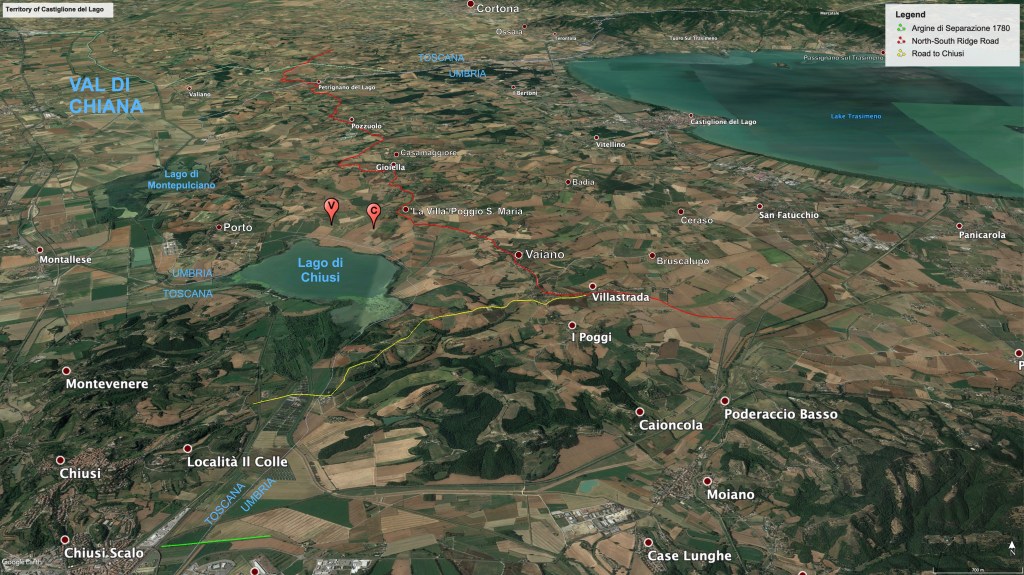

Lago Trasimeno sits between Perugia, Cortona, and Chiusi. Since the Etruscan period, those three cities have exerted their influence over the territory of the lake. The Trasimeno Regional Archaeology Project is investigating archaeological heritage in the territory west of Lago Trasimeno, principally within the Comune of Castiglione del Lago (see Fig. 2 below). This page reviews the geological and environmental formation of the area in order to appreciate better its historical development.

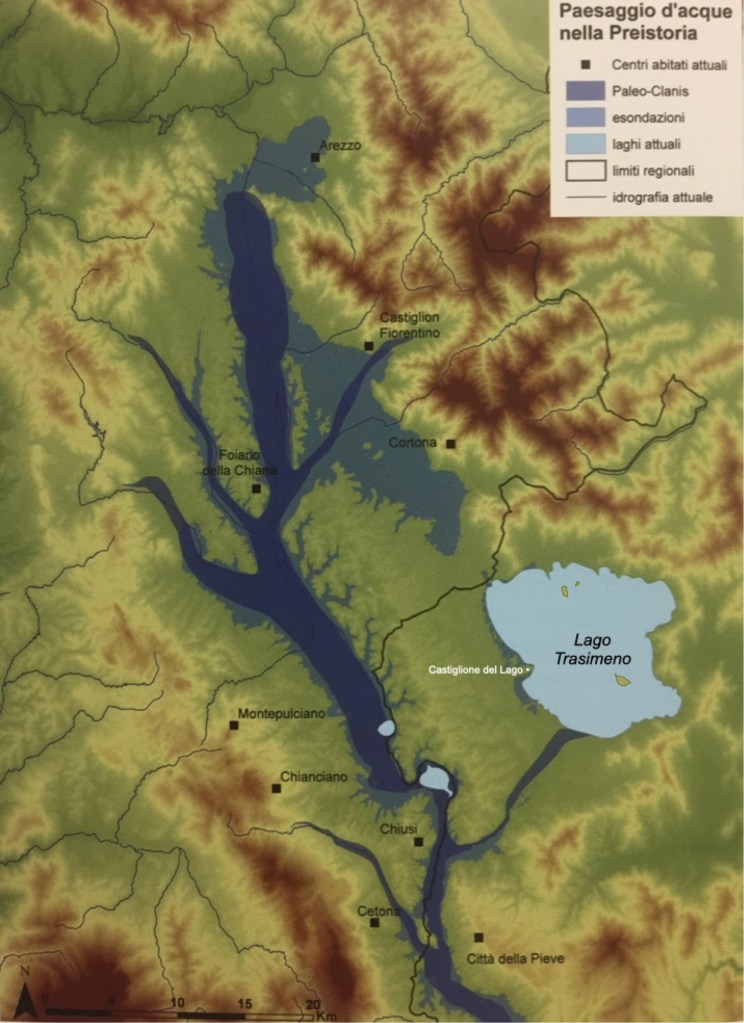

Rolling hills mostly comprise this Comune between Lago Trasimeno on the east, and on the west, the Valdichiana—the drained plain of the Chiana (ancient Clanis) river. Two shallow lakes, Lago di Montepulciano and Lago di Chiusi, essentially represent bulges in that water course and are remnants of the vast marshland that occupied this area in the Medieval period (more about this below). The archaeologist Bianchi Bandinelli called this the “zona tra i laghi,” i.e., the “district between the lakes” (1925: 513). The now-canalized course of the Tresa river roughly forms the southern limit of the territory. The north edge is marked by the modern border between Umbria and Tuscany, although in antiquity, this entire area was Etruscan, as far as the Tiber River to the east.

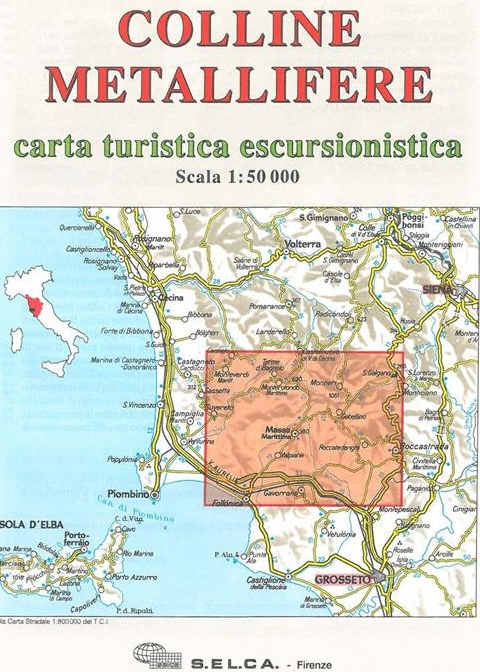

Forty-five and twenty-seven km to the southwest of Castiglione del Lago, respectively, rise the peaks of Monte Amiata (volcanic, a source of obsidian) and Monte Cetona (a limestone landmark); see Fig. 3.

For our purposes, we will begin our story of the geological history of this area just after the asteroid impact that extinguished the dinosaurs, ca. 66 million years ago (Mya). A long process of sedimentary accumulation and compression then began to occur in the deep waters of the western Tethys Sea, forming a stratum belonging to the ‘Ligurian Domain‘. Sand, silt, mud, lime and the shell fragments of sea creatures (comprised of calcium carbonate, CaCO3) slid and sank down, swirled around the ocean bottom, mixed and finally settled variously over the ocean crust into layers of limestone, sandstone, mudrocks, marls, flysch, etc.

The plates of Africa and Arabia (roughly speaking) swung counter-clockwise against the European plate to close off the eastern end of the sea and create the Mediterranean over the next 50+ million years (see the animation in Fig. 4 above). This clash of crusts caused orogeny (mountain-building). To the southwest, along the Tuscan coast (Fig. 5), the deformation facilitated the exposure of a wide and rich array of metals and minerals in the area called the ‘Colline Metallifere,’ the ‘Metal-bearing Hills,’ which have been exploited over the last 5000 years. These metals were critical to ancient trade: “ore deposits of pyrite, Fe, Cu-Pb-Zn, Ag, Sb, Hg, Sn and Au [whose] occurrence is related to hydrothermal fluids circulating along extensional faults that affect the bedrock following the emplacement of Plio-Quaternary magmatic bodies.” (Pieruccini et al., 2018: 19).

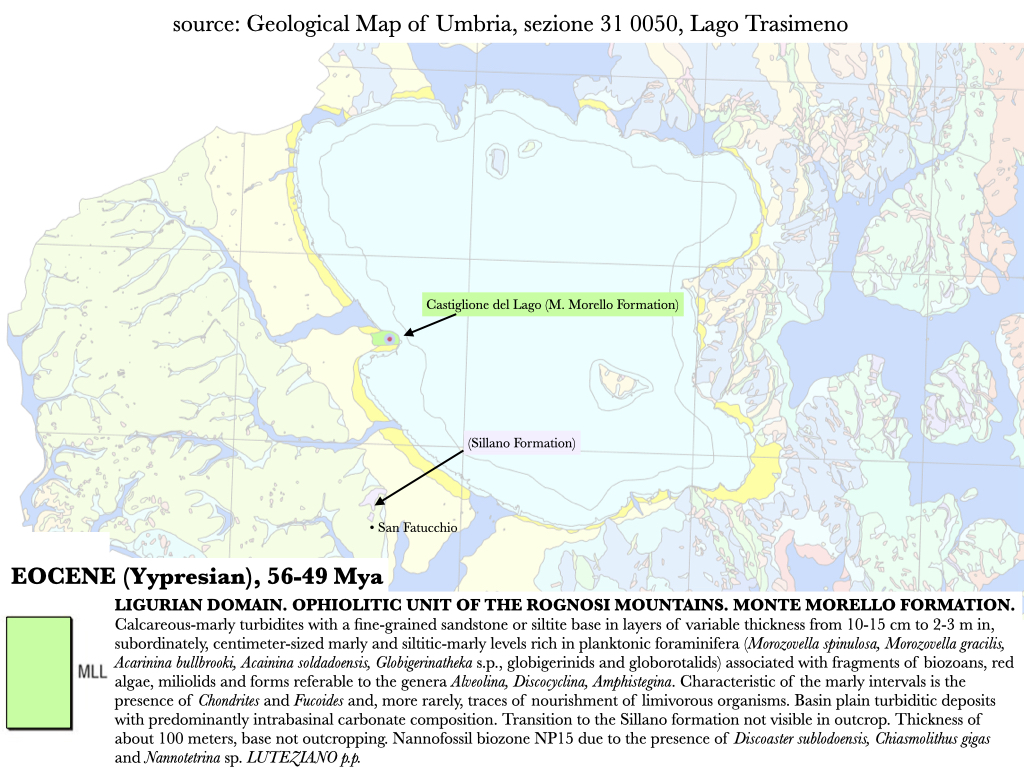

As orogeny occurred near Trasimeno, the originally oceanic Ligurian Domain layer (ca. 66-49 Mya) was compacted, thrust upward and folded over later Tuscan (Macigno Formation, ca. 30-23 Mya) and Umbrian-Marche (Marnoso-Arenacea Formation, ca. 19-17 Mya) turbidites (rocks formed by dense, sediment-laden water currents) to the east, rising onto dry land (Gasperini 2010: 165-66). In other words—and this is critically important—a few rock formations west and southwest of Trasimeno, belonging to what is called ‘External Ligurian Succession,’ lie on top of at least two thick layers of younger rocks, an inversion of normal stratigraphy (see Fig. 11 below)!

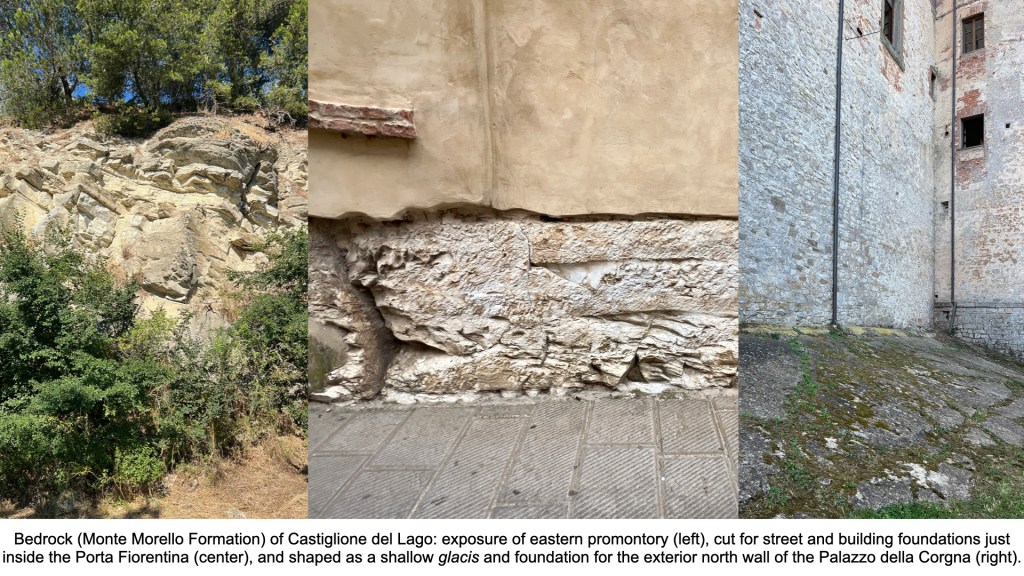

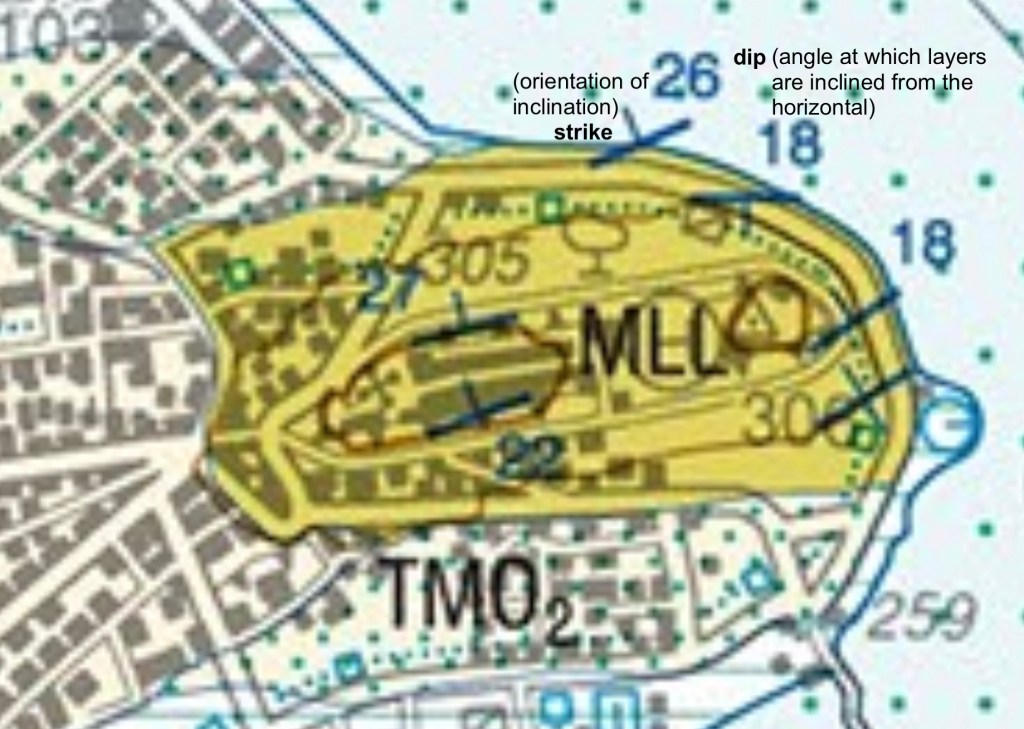

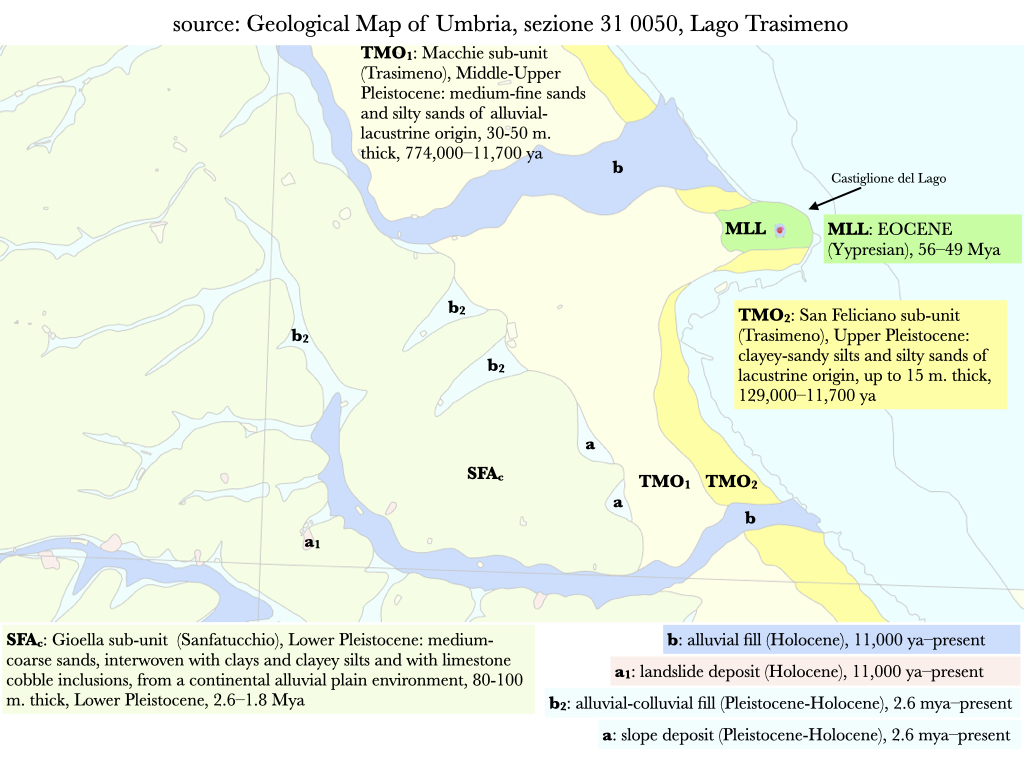

Today, this External Ligurian Succession is visible in just two outcrops (Fig. 6 below): one just north of San Fatucchio, of the Sillano Formation (Paleocene Epoch, ca. 66-56 Mya), and one of the Monte Morello Formation (Eocene Epoch, ca. 56-49 Mya), which comprises the rocky promontory of Castiglione del Lago.

At Castiglione del Lago, the outcrop, not more than 100 m. thick, comprises layers of calcareous-marly turbidites with a fine-grained sandstone or siltite base (Servizio Geologico D’Italia, 2009) that alternate in bands of white to light brown marly limestones, grey-yellowish calcarenites, and shales (Nirta et al., 2005). In some areas of Tuscany, this formation is known as Pietra Alberese, and is a common and valued building stone (Fratini et al., 2022). The stone for the historical buildings, town walls, and castle of Castiglione del Lago was quarried from this local bedrock. The lower part of this outcrop, on the southern side of the hill, is yellowish-grey white (Fig. 7 below, left), grading to, and overlapped by, whitish-grey stone on the northern side (Fig. 7 below, right).

The angle (dip) of the layers comprising the Monte Morello Formation of the promontory varies from 18-27 degrees from horizontal (Figs 7-8).

Surrounding these rocky outcrops, however, are far, far younger sediments of fluvial (river), colluvial (hill-slope), and lacustrine (lake) origin (see Fig. 9 below). Let’s see how all this developed.

Circa 13 million years ago, when the tectonic compression that brought about the initial formation of the northern Apennines had faded out, the situation around Trasimeno looked like in Fig. 11 (a) below. Some rocks of the External Ligurian Succession (green in the diagram) were exposed, having folded over the younger Tuscan and Umbria-Marche turbidites below, as described above. Eventually the connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean closed off, leading to massive evaporation of the Sea (the Messinian Salinity Crisis, ca. 5.97-5.33 Mya) and the accumulation of deep layers of salt at the bottom.

At Trasimeno, the exposed Ligurian Domain layers were then subject to massive erosion in deep valleys that ran NNW-SSE (parallel to the new mountain range). This erosion isolated some outcrops of the Ligurian domain—like the promontory of Castiglione del Lago; Fig. 11 (b) gives an example of what that would have looked like. In sum, an outcrop of older rock (Ligurian) lay on top of younger rocks (Tuscan and Umbria-Marche turbidites), and became isolated from surrounding geology by erosion. The outcrop of Castiglione del Lago therefore seems to be a klippe (Fig. 10 below).

A klippe can facilitate the formation of a freshwater spring, as water can find its way along the interface between the older top layer and younger lower layer, emerging to the surface through fissures. Springs are often the location of worship; klippes and springs exist together at both the sanctuary of Zeus on Mt. Lykaion and the Athenian Acropolis in Greece. The question of a spring is extremely important for the interpretation of our archaeological site on the south slope of the town.

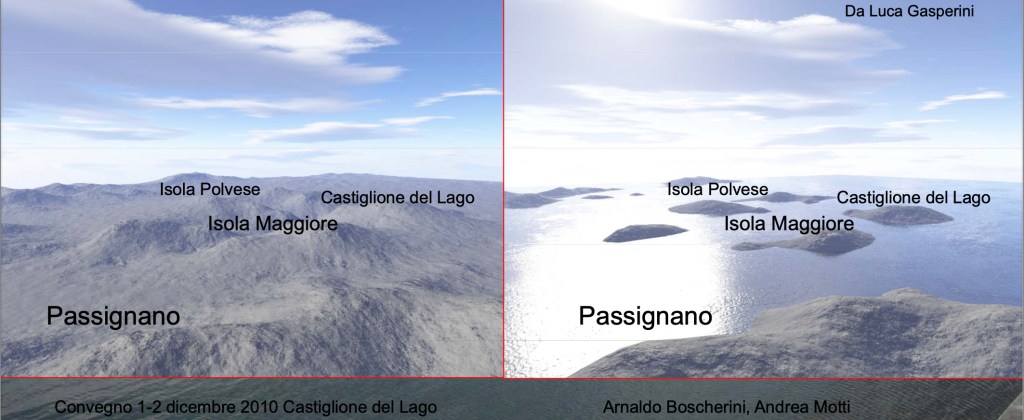

Eventually the connection between Gibraltar and Morocco was severed, the Atlantic Ocean poured in (the Zanclean Megaflood, ca. 5.33 Mya) and seawater poured up the eroded valleys on the west coast of Italy, forming an embayment: Fig. 11 (c) in the diagram above, and as shown in Figs. 12-13 below. The shift from Fig. 11 (b) to (c) can be seen in a reconstruction by Luca Gasperini (Fig. 12), in which the promontory of Castiglione del Lago was for some time an island in that embayment:

During the Late Pliocene–Early Pleistocene (ca. 2.6–1.8 Mya), the sea-level receded, the Apennine spine continued to rise, and the depression (low ground) around Lago Trasimeno continued to subside. Water drained to the nearby sea through a broad lake that became a river valley—Fig. 11 (d), and as reconstructed in Fig. 14 below.

Marine and continental braided fluvial channels deposited and mixed alternating bands of clays and sand west of the developing lake basin (the SFAc unit shown in the Detail of the Castiglione del Lago promontory map above, Fig. 9). Continuing tectonic uplift caused the terrain to angle downward from northwest to southeast with riverine tracks that drained southward (Bizarri et al. 2011). As uplift, drainage, and drying progressed during the Middle-Upper Paleolithic, when the first humans began to visit this area, remnant pockets of deeper water formed the district’s lakes (see Fig. 15 below). Essentially, those lakes are ‘puddles’ that are still drying up.

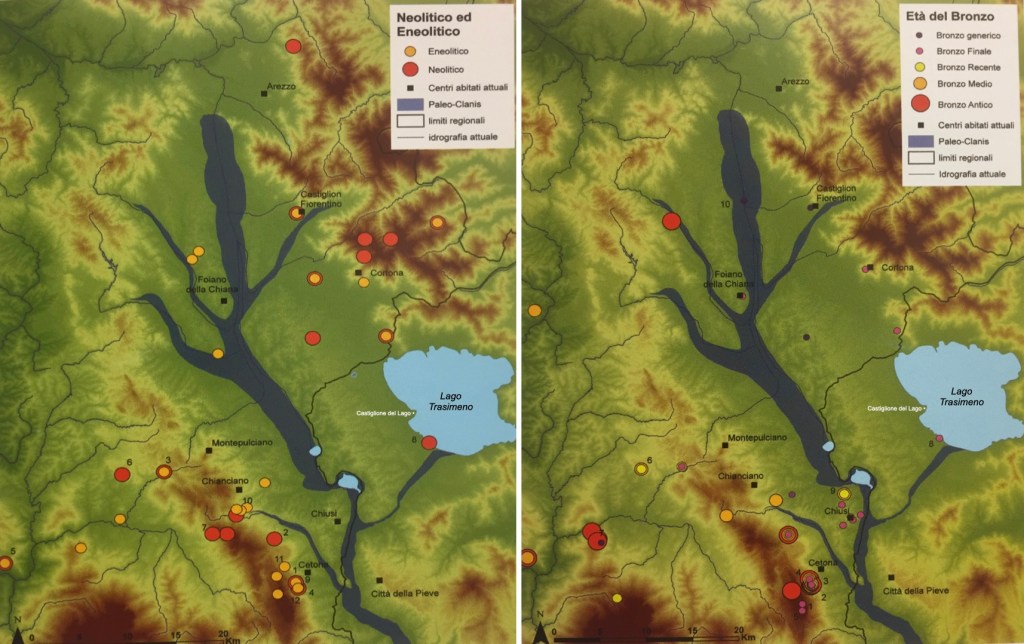

As the arrival of farming and herding practices arrived and developed during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, river and lake levels continued to fluctuate within stabilizing channels and beds (see Figs 16-17 below). Unfortunately, published detailed archaeological evidence for these periods in the Chiana-Trasimeno area remains relatively sparse.

Outside the major centers of Chiusi and Cortona, the situation is not much improved during the Villanovan and early Etruscan periods. We hope that our project will eventually contribute to improved understanding of these early periods. We do know that the west-east watershed between the Chiana River valley to the west and Lago Trasimeno to the east became important during the Etruscan era as a communication route between Chiusi and Cortona (see Fig. 18 below).

The current shape of the terrain largely resembles that in place ca. 500 BC (Battino 2014). However, during the Etruscan and Roman periods, the river they called the Clanis (today’s Chiana) ran sluggishly southward, widening into areas of open water today called Lago di Montepulciano and Lago di Chiusi. The Clanis eventually continued into the Tiber river just to the southeast of Velzna/Volsinii Veteres (Orvieto), on its way to Rome (Talbert 2000, Map 42). There is evidence that the Romans managed the water flow of the Clanis, but when imperial maintenance ceased, and the erosion caused by intensive agriculture and deforestation increased sedimentation, the valley began to become marshy, and an ideal breeding ground for malarial mosquitoes (see Figs 19-20 below). Populations moved away to higher ground.

Perugia began to redevelop the territory of Castiglione del Lago after 1184, building the castle and town walls in the 12th-13th centuries (significantly damaging the Via Belvedere site in the process), and clearing land for agriculture and settlement. Meanwhile Florence, after it gained control of the Valdichiana in the years around 1400, considered how to make it healthy and agriculturally productive once more, as well as a viable pilgrimage route to Rome (Chao 2022). Leonardo da Vinci was one of several experts enjoined to find a solution, and he drew up the birds-eye map (Fig. 21 below) to assess the situation of the flooded valley. Actual progress was intermittent.

In 1780 the Papal States and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany established the Argine di Separazione, “Levee of Separation,” at Chiusi Scalo (marked in green on Fig. 18 above). The waters of Lago di Chiusi and the northern section of the Chiana now drain northward into the Arno River as engineered by the massive 19th century land reclamation project directed by Fossombroni and Manetti (Fossombroni 1835). The drained valley bottom, managed with care hydrologically, has since proved reliably abundant.

Bibliography

Batino, S., 2014. “Letture geoarcheologiche nel paesaggio urbano e periurbano della Val di Chiana chiusina,” in Atti del Convegno ‘Dialogo intorno al Paesaggio’, Culture, Territori, Linguaggi 4: 184-95.

Bianchi Bandinelli, R., 1925. “Clusium: ricerche archeologiche e topografiche su Chiusi e il suo territorio in età etrusca,” Monumenti Antichi dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei 30: 210-578.

Bizzarri, R., Baldanza, A., and Argenti, P., 2011. “Plio-Quartenary paleoenvironmental evolution across western Umbria and Tuscany,” Il Quaternario 24: 81-83.

Boscherini, A. and Motti, A., 2010. “Il contesto geologico del Lago Trasimeno.” Convegno, Castiglione del Lago, 1-2 dicembre. https://www.arpa.umbria.it/resources/documenti/convegno-trasimeno/motti.pdf

Chao, K. 2022. “Valdichiana and the Rise of Florence in the Late Fourteenth and Early Fifteenth Centuries: A Road to Rome, a Road to Territorial Power,” Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 48.2 (2022) 21-45.

Caricchi, C., and Rinaldo Barchi, M. 2020. “La storia geologica del lago Trasimeno,” INGVambiente. https://ingvambiente.com/2020/12/14/la-storia-geologica-del-lago-trasimeno/.

Dallai, L., Pizziolo, G. and Sarti, L., 2011. La Chiana dal mare alle bonifiche. Storia di un fiume invisibile, exhibition catalogue (Montepulciano, 31 July–9 October 2011), SEB Editori.

Fossombroni, V., 1835. Memorie idraulico storiche sopra la Val-di-Chiana. 2 vols., 3rd ed. Montepulciano, Angiolo Fiumi.

Fratini, F. et al., 2022. “Pietra Alberese: from Traditional Building Material of the Tuscan Countryside to the Present Use (Tuscany, Italy),” Geoheritage 14.51.

Gasperini L. et al. 2010. “Tectonostratigraphy of Lake Trasimeno (Italy) and the geological evolution of the Northern Apennines,” Tectonophysics 492: 164-74.

Nirta, G. et al., 2005. “The Ligurian Units of Southern Tuscany,” Boll. Soc. Geol. It., Volume Speciale n. 3, 29-54.

Pieruccuni, P. et al., 2018. “Changing landscapes in the Colline Metallifere (southern Tuscany, Italy): early medieval palaeohydrology and land management along the Pecora river valley,” in G. Bianchi, R. Hodges, eds, Origins of a new economic union (7th-12th centuries): preliminary results of the nEU-Med project: October 2015-March 2017, 19-28. Sesto Fiorentino, All’Insegna del Giglio.

Servizio Geologico D’Italia, 2009. Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1:50,000, F. 310 Passignano sul Trasimeno, ISPRA, Rome.

Talbert, R.J.A., ed., 2000. Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton, Princeton University Press.