On 4 July 2022, a member of our team felt and heard the clang of metal-on-metal when their pickaxe struck the tail fin belonging to a British 4.2″, 20-lb. mortar embedded in the ground on the east edge of trench L10 in the Delta sector of the Ranciano dig site (see photo, right). We cleared the area, and our excavation was abandoned. But how and when did the mortar get there? We began to investigate what happened during the Second World War, and learned about the Battle of Ranciano, which took place on 24 June, 1944.

(photo: Pedar Foss)

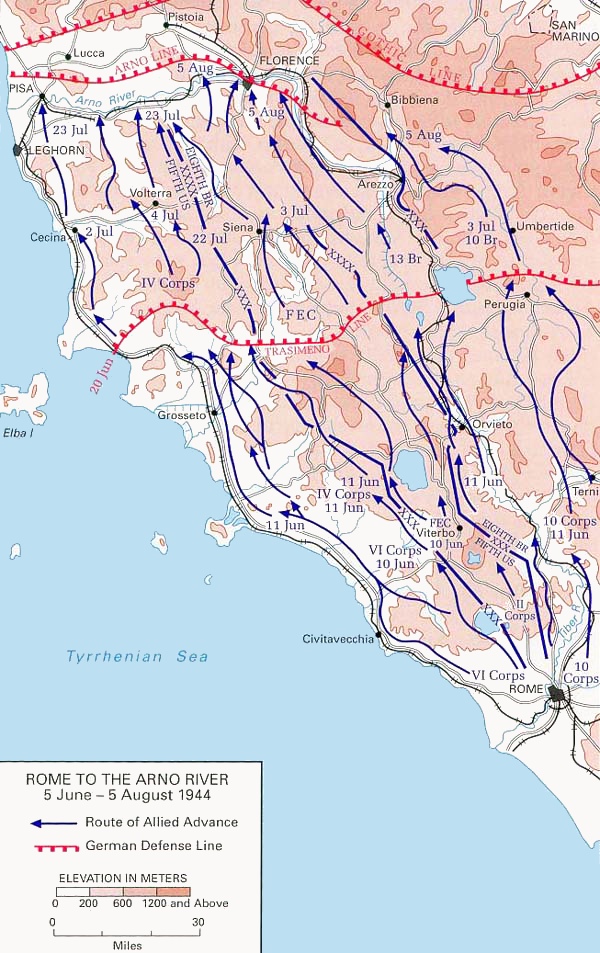

After the Allies captured Rome on 4 June 1944, German forces retreated northward, and attempted to slow Allied progress by establishing a series of east-west defensive positions (the “Trasimene Line”) across Tuscany and Umbria that used Lago Trasimeno as part of the blocking strategy (see map, left).

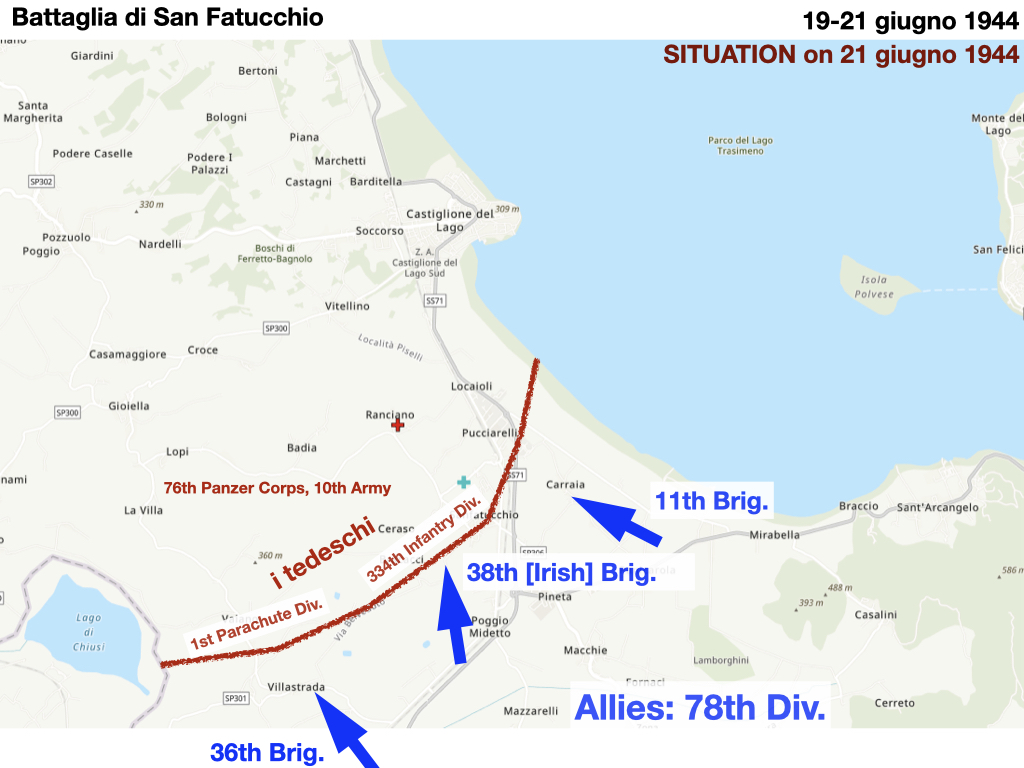

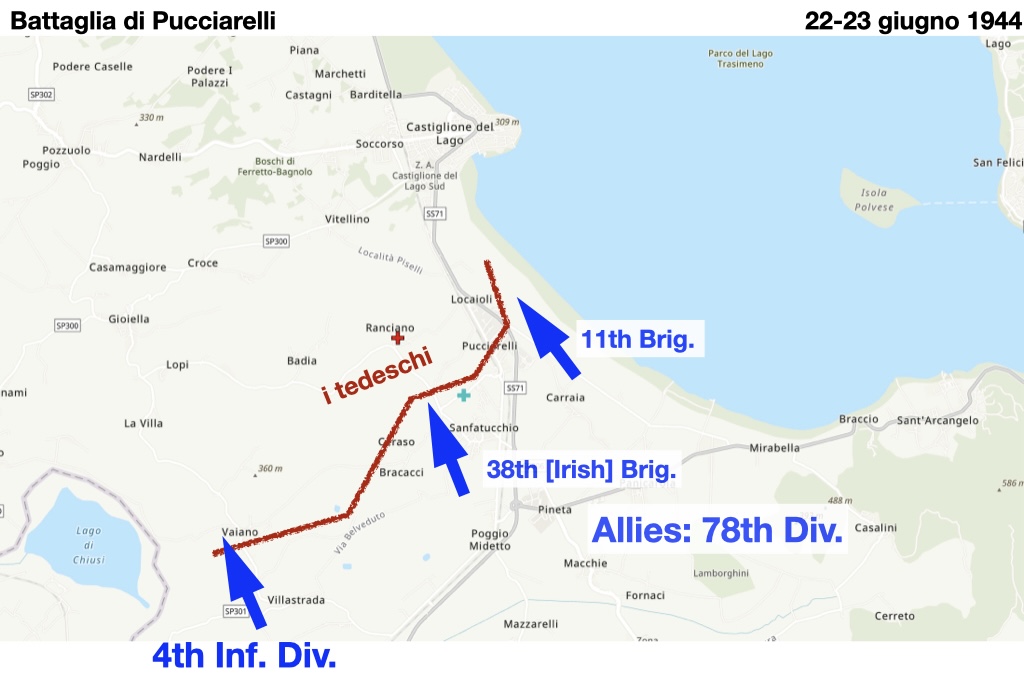

From 17-29 June, fierce fighting occurred on both sides of the lake involving some 60,000 men. To the west, difficult battles at San Fatucchio (19-21 June) and Pucciarelli (22-23 June) involved in particular the 38th (Irish) Brigade of the 78th Infantry Division (see maps below).

(map, left: Wikimedia [Laurie, Clayton D. Rome-Arno 1944, CMH Online bookshelves: WWII Campaigns, Washington: US Army Center of Military History CMH Pub 72-20, Page 24])

(three maps below: Pedar Foss, using basemap data from ArcGIS, revised by J.K. Dethick)

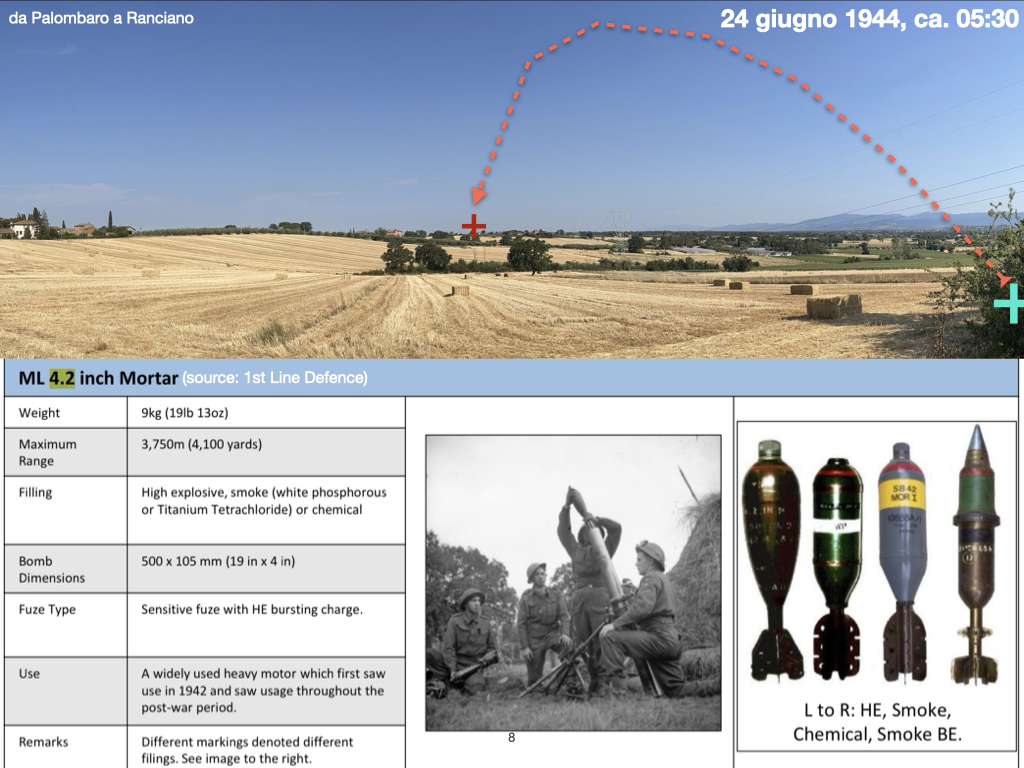

On the morning of 24 June, units of the London Irish Rifles, the Inniskilling Fusiliers (known as the “Skins”) and the Royal Irish Fusiliers (the “Faughs”) attacked German forces embedded in the hamlet of Ranciano. Soldiers’ diaries survive; they describe a mortar barrage at 5:30 am; during the advance along the west side of the lake, “firing a record total of over four thousand rounds, the mortar platoon wore out most of their mortars.”

Based on the angle and orientation of the tail fin, we estimated the firing location, which matched pretty well the written accounts:

(archival aerial photo: Istituto Geografico Militare, 1941)

The hypothesized firing position can be seen below, along with a description of the mortar type; the one we found would either have been high-explosive or smoke. The tail fin proved to be the only part that survived, as the Italian army unit that defuses old ordinance discovered (the relevant units defuse thousands of items each year). So in the end there was no real danger, but we did not know it at the time, and in any case, it seemed wise not to continue working at a location that, given the intensity of the exchange that June morning, may well have other, intact and more perilous, remnants of the war (we did recover various other small fragments of fuses and casings).

(photo: Pedar Foss; chart below: 1st Line Defence)

The find proved to be a good object lesson that archaeology often delivers the unexpected, and those surprises may be as intriguing as the intended targets of one’s research project.

For more on the battle, consult Janet Kinrade Dethick’s The Trasimene Line (rev. ed.), Fondazione Ranieri di Sorbello, 2012, available at the bookshop in the centro storico of Castiglione del Lago. Special thanks to her for vetting this page.